Watching the newest Disney movie, Moana, was very much like watching women pounding their fists against glass ceilings in feeble attempts to be heard as they follow their instincts for solving real-life problems. Moana is a young Princess from the South Pacific, destined to follow in her father’s footsteps as Chief of her tribe, and while her father entrusts her with this responsibility, going as far as to train her for her pre-ordained leadership role, he does everything in his power to stunt her efforts at individuality and independence.

Since she was a toddler, Moana was called to the sea and chosen by the sea to save her people, who are facing famine and destruction. Her instincts tell her that the sea is the path towards finding herself, her power, and the solution to her tribe’s ills. She attempts to follow these instincts, her gut feelings, for the sea constantly pulls her into its depths, but her father keeps standing in her way, telling her she doesn’t know what she’s doing, that it’s dangerous, that her place is among her people, at home, collecting coconuts and tending to the needs of her tribe. To be a caretaker, a mother to her land and followers, and not the adventurer, the voyager, she discovers is in her blood and in her tribe’s history.

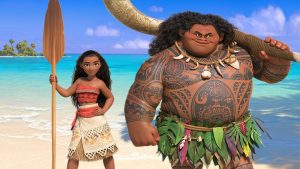

But the father is not the only hulking male figure of patriarchy that stands in her way. Another is Maui, the demigod who ruined her tribe’s future when he stole Te Fiti’s heart (a green pounamu stone); Te Fiti is the goddess that created all life, and when Maui stole her heart, she became vengeful, cursing all the islands she created and the natural resources with which she imbued them. Moana resolves to find Maui and force him to return the stone he stole to Te Fiti. Then all will return to the way it should be.

According to directors Ron Clements and John Musker, “We saw this as a hero’s journey, a coming-of-age story, in a different tradition than the princess stories,…I don’t know that any of the other princesses we’ve been involved with we’d describe as badass” (qtd. in Berman). Moana is badass. She is the antithesis of all the princess stories that Disney has profited from. And thankfully, this is a story that does not revolve around love and romance, as most Disney stories usually do. But what these directors are not aware of is that they set her up not against natural forces, but rather, patriarchal forces. And these are forces that all women have to contend with — in the home and in the workplace — as they endeavor to find their own place in life and in the professional world.

Moana’s character, despite her teen age status, is strong, confident, and determined. Throughout the story, she has to combat monsters and gigantic crabs out to kill her, violent seas that make her voyage difficult, and natural forces that impede her travels. As difficult as these seem to be for us, they’re the easiest parts of a journey designed to save her people. The most difficult is grappling against patriarchal forces that remind her she is “just” a girl, “just” a princess, “just” almost-something-but-not-quite-there. This was the most difficult part to watch, for it was very much like watching a vibrant light get flicked off by very large, masculine, and entitled thumbs.

Both Maui, the demigod, and Tui, her father, are hulking, masculine figures. They’re tall, muscularly built, and their voices and words garner submission. One is a demigod, the other is the Chief and her father, but they both represent the authoritative power and command that comes with patriarchy — with men in power. They each take turns constantly pressing her down, suppressing her voice and volition, with physical and verbal force. Moana’s greatest struggle is to fight against them for her own voice to be heard, her own strength to be realized, above their negative and over-powering resistance to her problem-solving tactics. Throughout the film, Moana knows how to solve the problem of decaying land and food, and she knows the answer lies in going beyond the reef, but her father’s fears attack her resolve again and again with such compulsion that she is forced to submit to him.

Similarly, once she’s past the reef, on her own, she has to fight against the powers and selfish forcefulness of the demigod that entombs and abandons her in a cave, steals her sailboat, throws her into the sea more times than is imaginable — all the while laughing — uses his physical strength against her, reminds her of her flaws throughout the story, and abandons her again when he fears his magic shape-shifting hook will be destroyed by her ambition to correct his mistakes. Child-like and petulant, this demigod becomes the greatest challenge that she has to overcome in order to solve the problems of her people. Standing up to him, she is fighting against patriarchy and masculinity alike, wrangling against the constant badgering and belittling that is every woman’s surest battle in life, and Moana’s struggle is no different, as he continually renders her to tears and self-doubt. Her greatest power comes not in solving problems or being creative about solving problems or battling monsters or ambition or gumption, but in fighting against the men that stand in her way with physical and emotional force just to shut her up, stunt her growth and potential, and put her in her place.

The only two people that support Moana and see the full extent of her potential are her mother and her grandmother. Her mother helps her pack food the night she decides to leave the island, and her grandmother confirms that their people are voyagers and that Moana’s unspoken call to the sea is part of her heritage. If not for these two women, and the grandmother in particular, who kept returning to remind Moana of her strength, Moana would not have been able to overcome the ferocity imposed upon her by the two fiercest men in her life. How could she — a 16-year-old girl pinned against a demigod and a Chief/father — two imposing figures who cast a long shadow of authority and power over her?

Clements and Musker believe that they have put together a film with an empowered princess for girl audiences, but they still designed this film through the relentless male gaze that plagues all works created by men. They don’t see what we girls and women see: one girl set up against the will of two powerful and patriarchal figures. In many ways, this is what many females experience as they come of age. Our most persistent battle is not finding ourselves or solving our problems, but fighting against patriarchal norms that come at us from every male, every male-dominated industry, reminding us that we have to fight harder, yell louder, work longer just to be heard, just to achieve what we know is rightfully ours: free will and volition.

One thought on “Feminist Gaze: Moana, Patriarchy, and the Glass Ceiling”